This is an edited version of a longer conversation. See the full talk on YouTube here.

On Curating at ICP

Karolina Chojnowska: You are currently the Senior Curator and Director of Exhibitions and Collections at ICP. Can you tell us a little bit about your day to day and your responsibilities as the senior creator and director of exhibitions and collections?

Elisabeth Sherman: When anybody ever asks a curator or a museum administrator about their day-to-day, it's like, well, which day? What hour?

Sometimes I'm in meetings all day. We just finished installing our three new exhibitions. So we spent two and a half weeks on the floor installing shows. Two of the shows were not curated by me, so I was popping in and out, checking in with the team, making sure everything was running smoothly. Also co-curating my own show.

So really it depends on placing the work, you know, figuring out all of the problems, running back to the office, answering emails, sitting in meetings, doing studio visits, going to galleries, taking patrons around, writing. It runs the gamut.

And every day and every week is completely different, which honestly is part of what I love about it.

KC: It seems fun. You’re never just constantly at your desk. You're always kind of everywhere. You’re never bored.

ES: Yeah. A little less zoom I would take.

KC: What would you like to see, or what would you like to achieve, while at ICP in this role?

ES: I mean, I really feel like this season of exhibitions [Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, American Job: 1940-2011, To Conjure: New Archives in Recent Photography]—granted I'm talking about exhibitions and my role does oversee so much more than just that—shows how you can respect the past and bring new interpretations to it that feel really relevant now.

Both the past of the history of photography, but also the past of an institution's history while writing a new chapter. Being able to connect across those interests is really important to me.

We have these shows that are really central to ICP's identity while writing new chapters all in one season. If we can achieve that with the collection, if we can achieve that with our public programs–which I think we are, and the audience is responding–that to me is success.

Weegee: Society of the Spectacle and To Conjure: New Archives in Recent Photography. Image © Will Ragozzino / scottruddevents.com

Photography as a Medium

KC: What would you say you find particularly interesting about photography as a medium?

ES: That it never stops changing. I love all media. I've curated exhibitions across all materials. I love craft.

But if you think about oil painting, it is essentially the same technology now that it was when humans first started using it.

Photography does not sit still. It's young. It's ever changing.

I always feel like when you try to define what is a photograph or what is photography, you try to pin it down and it slips right away.

Do you need a camera for photography? No. Do you need a darkroom for photography? No. Can photography be entirely computer generated? Yes. Can it be something that looks like a painting? Yes.

I think I got interested in contemporary art and artists so that I wouldn't be bored, so that my mind would continue to be pushed to expand, to take in new ideas. And because photography is so restless, it never sits still. How can you ever get bored?

Photography and AI

KC: There's a big conversation now around the introduction of AI to photography. What do we consider a photograph? Or, an image created by a human being versus AI—how do we judge them against each other?

ES: I do come from the kind of more expansive contemporary or perspective where I think artists are always going to use new tools. So, I don't really care that much, to be honest, what tools they use, as long as what they're creating is interesting and thought-provoking and a relevant commentary on the world we live in.

Where we get into conversations about photojournalism and documentary is where it gets much more divisive. And, understandably people really want know—where is the truth, is this a representation of truth?

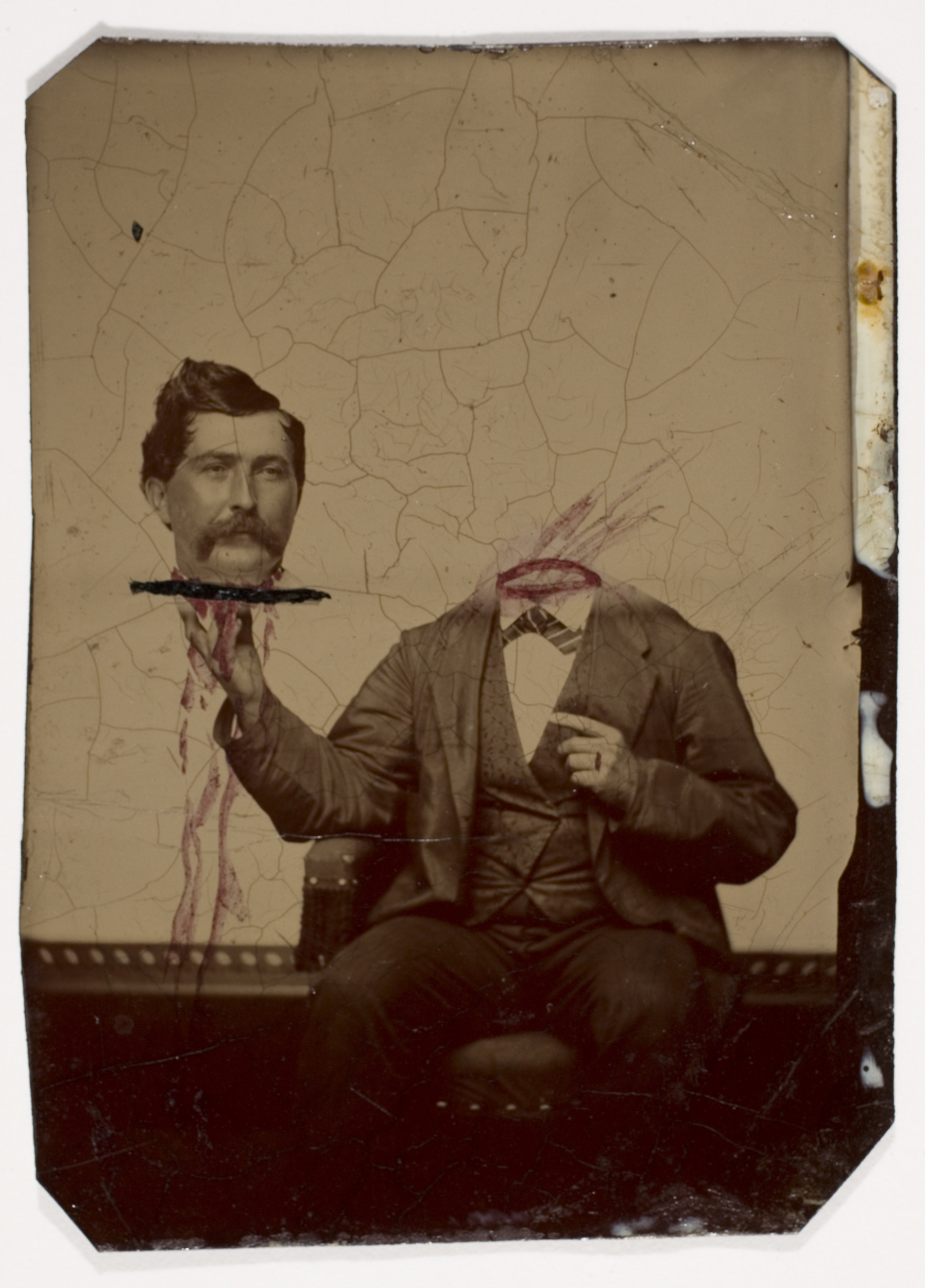

But if you really look at history, photography has always been manipulated from the very earliest days of the medium. We have daguerreotypes in our collection of a man holding his head on a platter or, you know, someone jumping off Tower Bridge in London to a cartoon boat below it.

Unidentified Photographer, [Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter], ca. 1865. Gift of Steven Kasher and Susan Spungen Kasher, 2008 (2008.81.15)

We can think about famous examples of news photography throughout history that people think are “true.” And then when you look at the contact sheet and you see the context of the picture was taken in, you realize that the framing, the editing told a different story than if you had been there and experienced it.

So I'm very concerned about truthfulness in our moment, but I don't think AI is going to ring the death knell of truthfulness. I think it's a problem that exists in every form. And we have to hold each other more accountable and not accuse the tools of being the ones creating the problems. The tools have changed, the impulse has not.

Advocating and Asking Questions

KC: I really love this quote that you said in the British Journal of Photography: "I keep my feminist principles and advocacy for all marginalized voices at the center of what I do."

ES: It will take sustained effort by all of those who support artists, including collectors, galleries, scholars, auction houses, foundations, residencies, and beyond, over a long time, to counteract the weight of history written by and for men.

I think it's so important for curators, who are effectively writing histories through their exhibitions and research that they do on these artists, to focus on the values that we need to see reflected in this world.

KC: Do you have any advice for incoming generations of women who are looking to work in the arts?

ES: Ask all the questions and listen to the answers. It may be hard to hear it, but really think about what kind of a life you want to have—your whole life. This is always what I say. When you're young, I think the only thing that feels solid is your career ambition, and so you put all your eggs in that basket.

But think about who you want to be and what kind of a life you want to have. What kind of a place do you want to live in? How do you want to be? Are you very social? Are you not very social? Or do you like socializing with your friends, but you don't like socializing for work?

Ask these questions of people who do these jobs, and listen to the answers, and try to choose a career path that matches the life you want to live. Not chasing a goal simply because it seems to be the most star-studded goal or the hardest thing to achieve.

KC: I think that's so important, and I'm glad that you mention that.

Because early on in my career, I was just kind of grabbing at things, looking at what sticks, and I wasn't really asking myself questions about where I see myself long-term in life. Because I think when you're young, you're just, you're not really thinking, you can't see.

ES: Exactly.

KC: And then also, have a check in with yourself at, like, every five or 10 years. The things that I wanted in my 20s, I don't want anymore. And I'm sure future me in 10 years will be different as well.

ES: One can only hope! I don’t want to stop changing.